This is a blog post from my Masters work which was conducted in 2018-19. It is a re-post from the original site where the blog was held and was only slightly adjusted to the new website. If you are interested in the larger project you can read the thesis here.

Escape games contain similarities to live-action roleplaying games (LARPs). Working on a smaller scale, with less participant buy in, escape rooms offer the chance for participants to engage players in a story. Role playing games involved imaginative play, asking players to take on a certain character (typically of their choice) and participate in a narrative. Escape games offer a central story and typically giving a choice in how much players want to perform since role-playing makes minor difference to the overall game.

In my own game I performed multiple roles. The role of Craig (and in one instance Carl); A corporate man who encouraged players to give five star reviews and make them as comfortable as possible in the play experience. Craig was overly energetic, super optimistic and positive antagonist, whose goal was to please each participant while enforcing company expectations. Consistently checking in on players, Craig managed game flow in the space acting as a surveillance figure “unintentionally” slowing player progress if he caught them doing things that they were not expected to do (such as solve the escape room).

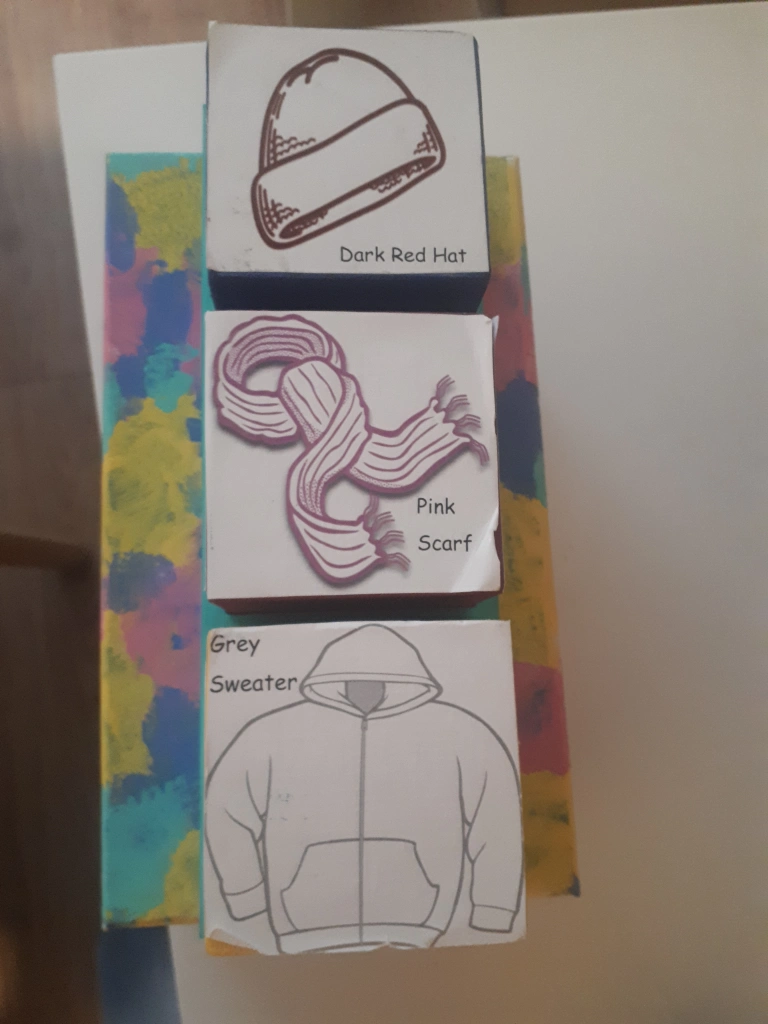

This puzzle box had players input an outfit which Craig subsequently wore. Doing so, was one of many instances where the game reflected player inputs in ever-prominent outputs.

I also played a mysterious CM, an ex-employee who left a note and phone in the room to communicate with players. CM was trying to expose Reactile (the company behind it all), but needed the help of the players to succeed. While players never officially meet CM, the character communicated through limited messages from beyond the gameroom. I slipped notes under the door, sent text messages to a phone, and even ‘hacked’ a surveillance feed to keep talking with participants. CM was counter to Craig, aiding players through hints and warnings, while also engaging in virtual dialogue if participants chose to.

The other two roles I “played” were not performative, rather I was a game manager and facilitated learning as an educator of sorts. I welcomed players to the game and project, I briefed them on the experience, and (occasionally during play) I would break character and help fix a broken aspect of the room (i.e. players had a correct combination that wasn’t working on a lock). As a manager, I had to balance being a performing individual and a ‘game master’, monitoring the experience to make sure the project was running smoothly. Finally, as an educator, I worked on guiding a debrief, talking about the metaphor used in the space, and curating conversation around digital personalization and players personal habits.

Each of these roles played out during a game experience, and each critical to the project’s success. Craig served multiple purposes. As a metaphor to surveillance and personalization structures, I would bring new materials, clues, and distractions into the room. Based on previous answers and preferences, Craig would bring certain products, or wear specific colours and styles of clothes as the game progressed. Additionally, to maintain the flow of the game and help teams focus on specific puzzles, Craig determined when certain materials could enter into the play experience. While, sometimes also trying to indirectly help ‘stuck’ players who struggled to communicate with CM, Craig’s main goal was monitoring game flow and presenting material back at players. CM was mainly a counternarrative, meant to push players to critique the game system. CM knew everything about the company and told players that if they needed help to ask. Most escape games offer hints, and CM helped circumvent the challenges of helping players while also attempting to distract them.

The counter roles of Craig and CM, established the entire structure of play, creating a power-tension for players to navigate. While I was concerned with being too much of a distraction and complication for players, the debriefs suggested otherwise. Players discussed their appreciation of Craig, actually hoping that Craig had a larger impact in the game. They wanted Craig to ‘catch’ them and make it more challenging. They liked the notion of being rewarded or punished depending on their ability to hide their actions from Craig. Having an element of imaginative play helped with immersion, and despite players not always participating with the performance, it was effective in engaging participants.

Comentarios